Genetic Mottled Skin Discoloration Risk Calculator

Your Risk Assessment

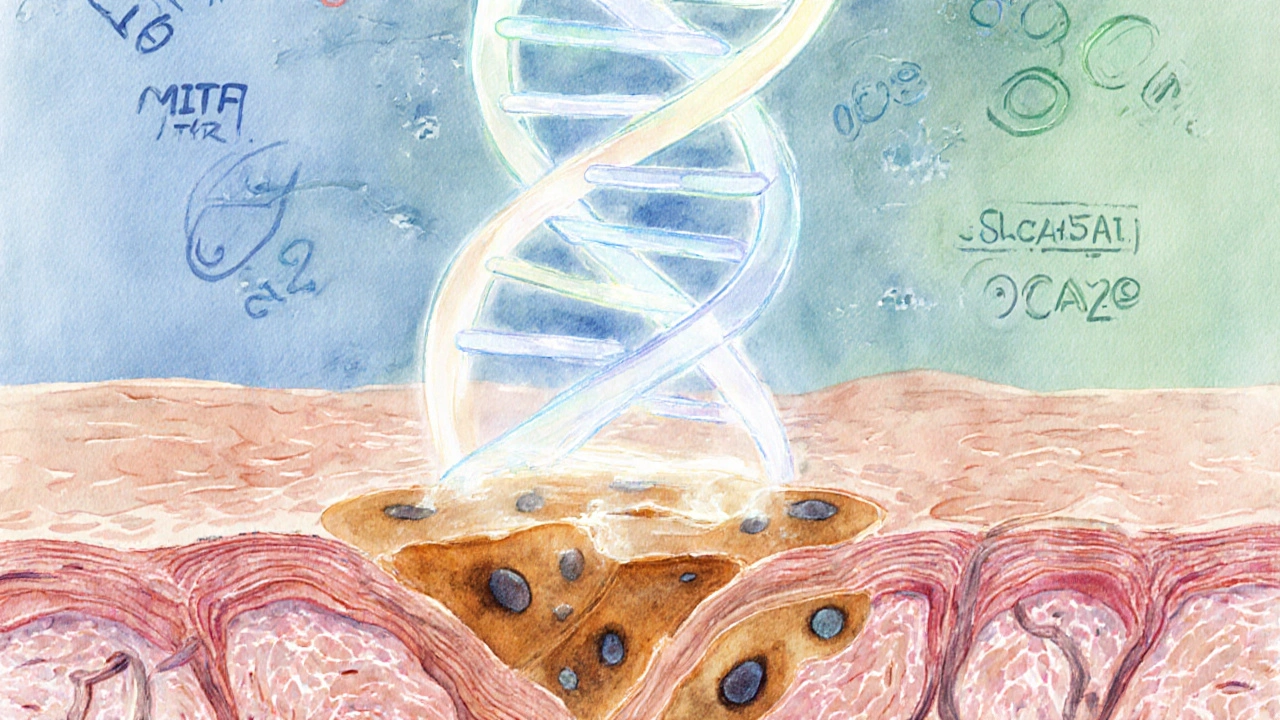

Key Genes Involved

MITF

Regulates melanocyte development

Autosomal DominantTYR

Enzyme for melanin synthesis

Autosomal RecessiveSLC45A2

Transports melanin precursors

Complex InheritanceOCA2

Influences melanosome pH

Autosomal RecessiveIf you're wondering about mottled skin discoloration genetics, you’re not alone. Many people notice patchy, marbled spots on their skin and wonder whether it runs in the family or if something they can change. This article breaks down what causes the mottled pattern, which genes are involved, how you can tell if you’re at risk, and what steps you can take to manage it.

What Is Mottled Skin Discoloration?

Mottled skin discoloration is a skin condition characterized by irregular, blotchy patches of lighter or darker pigment that create a marbled appearance. Unlike a uniform rash, the spots vary in size and shape, often forming a net‑like or lace pattern. The condition can appear anywhere on the body but is most common on the arms, legs, and torso.

The discoloration is usually harmless, but the visual contrast can cause self‑consciousness, especially when it appears on exposed areas.

Why Genetics Matter

Genetics plays a central role because the pigment‑producing cells-melanocytes-are controlled by a network of genes that dictate how much melanin they make, where they settle during development, and how they respond to environmental cues.

When a mutation disrupts any part of that network, the result can be uneven melanin distribution, leading to a mottled pattern.

Key Genes Behind the Mottling

The most frequently implicated genes include:

- MITF (Microphthalmia‑Associated Transcription Factor) - regulates melanocyte development and melanin synthesis. A single‑nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in MITF can reduce melanin output in localized skin regions.

- TYR (Tyrosinase) - the enzyme that converts tyrosine to melanin. Loss‑of‑function variants cause lighter patches.

- SLC45A2 - transports melanin precursors. Certain alleles are linked to reduced pigment in specific skin zones.

- OCA2 - influences melanosome pH, affecting melanin stability.

These genes don’t act alone; they interact with regulatory elements and epigenetic markers, which can amplify or dampen the visual effect.

How Inheritance Works

Inheritance patterns for mottled discoloration are diverse:

- Autosomal dominant: One copy of a mutated gene (e.g., MITF) can be enough to produce the condition. A parent with the trait has a 50% chance of passing it to each child.

- Autosomal recessive: Two copies of a defective gene (e.g., TYR) are required. Carriers are usually symptom‑free but can have affected children if both parents carry the mutation.

- Mosaicism: A post‑zygotic mutation occurs after fertilization, leading to two genetically distinct cell lines in the same individual. This explains why some people develop mottling only in limited body areas.

Because mosaicism can arise spontaneously, a family history may be absent even though genetics are at play.

Who Is at Risk?

Risk assessment blends family history, ethnicity, and personal health:

- Family history: A parent or sibling with mottled patches raises your odds, especially for dominant genes.

- Ethnicity: Certain variants are more common in European or East Asian populations, reflecting historic selection for skin tone.

- Age: Mosaic patterns often appear in childhood, while genetic predispositions may become evident in adolescence.

- Environmental triggers: UV exposure can accentuate existing pigment differences, making mottling more noticeable.

Testing and Diagnosis

Diagnosis starts with a visual exam by a dermatologist, who may use a Wood's lamp to highlight pigment differences. If genetics are suspected, the following tests help:

- DNA sequencing panel: Targets MITF, TYR, SLC45A2, OCA2, and other pigmentation genes. Results pinpoint pathogenic variants.

- Family pedigree analysis: Maps inheritance patterns across generations to confirm dominant, recessive, or mosaic origins.

- Skin biopsy: Rarely needed, but can differentiate mottling from inflammatory conditions like lupus.

Genetic counseling is recommended when a pathogenic variant is found, especially for family planning.

Managing Risk and Appearance

While you can’t change your DNA, several strategies reduce the visual impact and protect skin health:

- Sun protection: Broad‑spectrum sunscreen (SPF30+) prevents UV‑induced melanin hyper‑ or hypopigmentation.

- Topical camouflaging agents: Mineral‑based foundations match skin tone without irritating melanocytes.

- Laser therapy: Fractional lasers can stimulate melanin production in lighter patches, but results vary.

- Nutritional support: Adequate intake of vitaminD, copper, and tyrosine supports melanin synthesis.

Regular dermatologist visits ensure any changes are monitored, especially if new spots appear rapidly-a sign to rule out vascular conditions.

Comparison of Common Pigment Disorders

| Condition | Primary Cause | Key Genes | Typical Onset | Management Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Mottled Discoloration | Gene mutations affecting melanin production | MITF, TYR, SLC45A2, OCA2 | Childhood‑adolescence | Sun protection, cosmetic camouflage |

| Vitiligo | Autoimmune destruction of melanocytes | NLRP1, PTPN22 (immune‑related) | Any age, often before 30 | Topical steroids, phototherapy |

| Livedo Reticularis | Vascular filtering causing net‑like cyanosis | Not gene‑driven (often secondary) | Adult onset, may signal systemic disease | Address underlying cause, warm compresses |

Next Steps for Concerned Readers

1. Schedule a skin exam if you notice new or changing patches.

2. Ask your dermatologist about a targeted DNA panel if family history suggests a hereditary pattern.

3. Practice daily sun safety and consider cosmetic options that match your natural tone.

4. If a pathogenic variant is identified, arrange genetic counseling to discuss implications for relatives.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can mottled skin discoloration turn into melanoma?

Mottling caused by genetic pigment variation is not a precancerous condition. However, any new or changing lesion should be evaluated, as melanoma can sometimes mimic pigment changes.

Is a skin biopsy always required?

No. Most cases are diagnosed clinically. A biopsy is reserved for atypical presentations where infection, inflammation, or a vascular disorder is suspected.

Do lifestyle choices affect genetic mottling?

Lifestyle can influence how pronounced the patches appear. UV exposure, smoking, and poor nutrition can exacerbate pigment imbalance, while protection and a balanced diet may lessen contrast.

Can children inherit the condition even if parents show no symptoms?

Yes, especially with mosaicism. A post‑zygotic mutation can arise in the child alone, meaning parents appear unaffected.

Is there a cure?

There is no cure for the genetic basis, but treatments can improve appearance and protect skin health. Ongoing research into gene‑editing therapies may change this in the future.

angelica maria villadiego españa

October 6, 2025 AT 12:47I totally understand how overwhelming the genetics info can feel, but remember you’re more than a risk score.

Ted Whiteman

October 10, 2025 AT 09:21Wow, a risk calculator for skin spots? That sounds like a sci‑fi plot twist where the hero discovers a secret DNA code hidden in freckles. Honestly, the whole thing feels like the internet trying to turn every little shade difference into a drama. The real issue is that most of these scores oversimplify a complex trait, turning biology into a lottery ticket. Still, if it makes you think twice about sunburn, maybe it’s not a total waste of pixels.

Dustin Richards

October 14, 2025 AT 05:56It’s reassuring to see a tool that tries to break down the genetics behind mottled skin. While the math is simple, the reality is far more nuanced, so take the results as a conversation starter rather than a verdict. Consulting a dermatologist will give you the best personalized insight.

Vivian Yeong

October 18, 2025 AT 02:30The calculator oversimplifies inheritance patterns, especially the polygenic aspects of MITF and SLC45A2. A brief disclaimer can’t replace a thorough genetic counseling session.

suresh mishra

October 21, 2025 AT 23:04MITF is a transcription factor driving melanocyte development; mutations often follow an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning one copy can affect pigment production.

Reynolds Boone

October 25, 2025 AT 19:38UV exposure is a big modulator-high levels can amplify the visual impact of any underlying genetic predisposition, so consider sunscreen as a practical countermeasure.

Angelina Wong

October 29, 2025 AT 15:13Don’t let a number scare you; lifestyle tweaks like shade, sunscreen, and regular skin checks empower you to stay ahead of any changes.

Anthony Burchell

November 2, 2025 AT 11:47Honestly, I think these calculators are just click‑bait; they pull you in with flashy icons but give zero actionable advice beyond “see a doctor”.

Michelle Thibodeau

November 6, 2025 AT 08:21Reading through the genetics of mottled skin feels like opening a treasure chest of colorful stories about our ancestors.

Each gene-MITF, TYR, SLC45A2, OCA2-carries a tiny narrative of how our cells learned to paint us.

The calculator tries to sum up that epic saga into a tidy risk number, which is both ambitious and a bit naïve.

While I love the idea of democratizing genetic knowledge, the reality is that inheritance is a tangled web.

Autosomal dominant traits like MITF can show up in a single generation, yet environmental factors still play a starring role.

Recessive genes such as TYR often hide silently, only revealing themselves when two copies meet.

Complex inheritance, as seen with SLC45A2, reminds us that many shades of risk cannot be boiled down to a simple yes or no.

Your family history, like having a parent with mottled skin, adds a powerful clue, but it’s not the whole picture.

Ethnicity weaves its own influence, with European and East Asian backgrounds sometimes nudging the score higher.

Age matters too; younger skin can exhibit different patterns than mature skin, which is why the calculator adds points for children and teens.

And let’s not forget the sun-our biggest, brightest enemy when it comes to pigment disorders.

High UV exposure can amplify any genetic predisposition, turning a modest patch into a dramatic statement.

So, while the risk calculator offers a useful snapshot, think of it as a map, not the territory.

The true journey involves regular dermatologist visits, thoughtful sun protection, and staying curious about your own biology.

Embrace the data, but let your daily choices be the brushstrokes that define your skin’s story.

Patrick Fithen

November 10, 2025 AT 04:56The skin is a canvas and the genes are the palette we all share but each of us paints with his own light and shadow the interplay of nature and nurture creates a story no calculator can fully capture

Michael Leaño

November 14, 2025 AT 01:30Remember, knowledge is power-understanding your genetic risk can motivate you to adopt protective habits and keep your skin healthy for years to come.

Anirban Banerjee

November 17, 2025 AT 22:04I would like to extend my sincere appreciation to the original poster for compiling this informative resource; it serves as a commendable foundation for further discussion and professional consultation.

Mansi Mehra

November 21, 2025 AT 18:38While the content is generally accurate, the phrase “Your Risk Assessment” should be capitalised consistently and the disclaimer could be phrased more precisely: “This tool provides educational insights and does not substitute for medical advice.”

Jagdish Kumar

November 25, 2025 AT 15:13Ah, the elegant dance of melanin genes! One cannot help but admire the sophisticated choreography of MITF, TYR, and OCA2 as they waltz across the epidermal stage-truly a masterpiece worthy of scholarly applause.

Aminat OT

November 29, 2025 AT 11:47omg i cant even with all this science its like u r scared of a few freckles lol