When a pharmacist hands you a generic pill instead of the brand-name version, it’s not just a simple swap. Behind that decision is a complex financial system that determines how much the pharmacy gets paid, how much you pay out of pocket, and who makes money in the process. In 2025, over 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs. That’s up from just 33% in 1993. But here’s the catch: the more generics a pharmacy dispenses, the more it risks losing money - not because generics are cheap, but because how they’re paid for is broken.

How Pharmacies Get Paid for Generics

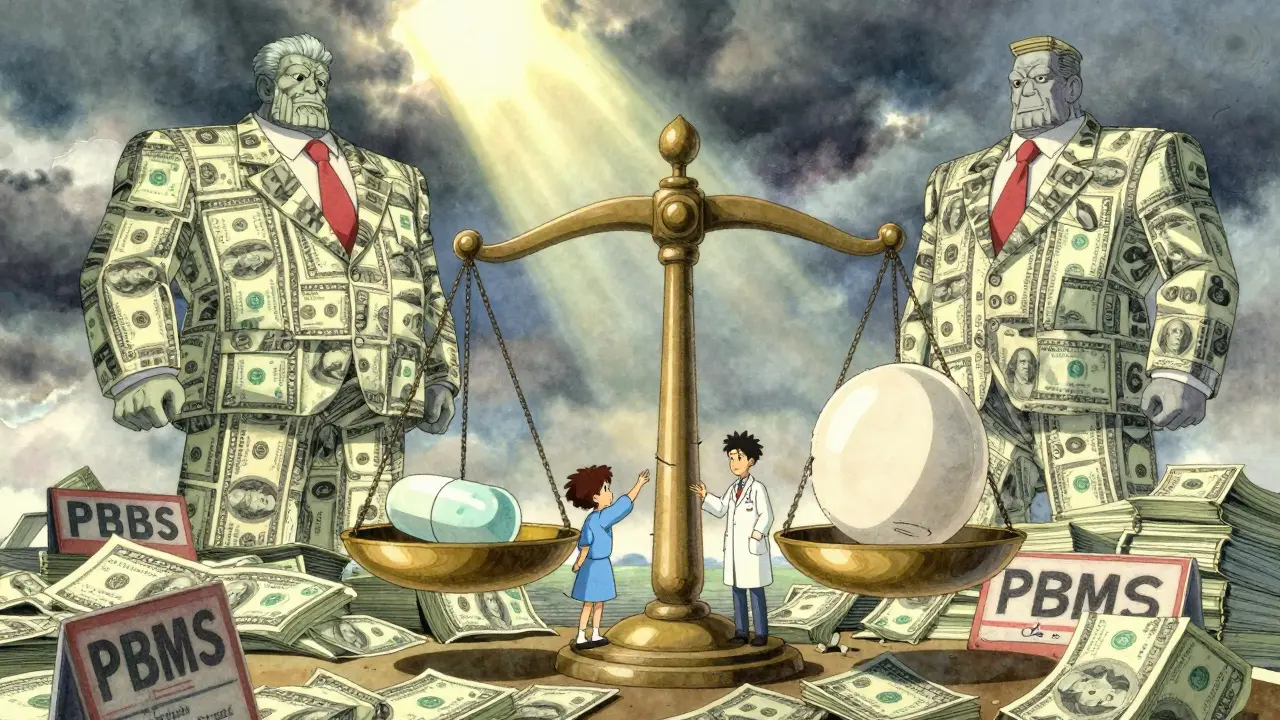

Pharmacies don’t make money because generics are cheaper. They make money because of the gap between what they pay for the drug and what they’re reimbursed. For brand-name drugs, reimbursement used to be based on the Average Wholesale Price (AWP), a number that had little to do with actual cost. Today, that’s mostly gone. For generics, reimbursement is tied to Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists - a list of prices set by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) that say, "This is the most we’ll pay for this generic."

Here’s how it works: A pharmacy buys a 30-day supply of generic lisinopril for $2.50. The MAC list says the PBM will reimburse $5.50. The pharmacy keeps $3.00 as profit. Sounds fair, right? But what if the PBM sets the MAC at $5.50 because they’re buying the same drug from a distributor for $3.00 - and then charging the insurance plan $8.00? That $5.00 difference is called "spread pricing," and it’s where PBMs make billions. The pharmacy gets $5.50, but the real cost to the system is $8.00. The patient pays their $5 copay, and the insurer pays the rest. The pharmacy never sees the full picture.

Why Generic Substitution Isn’t Always Cheaper

Generic substitution sounds like a win-win: same drug, lower price. But not all generics are equal. Two drugs in the same therapeutic class - say, two different brands of metformin - can have wildly different prices, even though they do the exact same thing. Studies show that some generic versions cost 20 times more than others in the same class. Why? Because PBMs put the higher-priced version on their formulary. It’s not about clinical effectiveness. It’s about profit margins.

Take a case from 2023: A patient was switched from a $1.20 generic metformin to a $24.50 generic version because that’s the one the PBM’s MAC list favored. The pharmacy made more money on the $24.50 version - even though the cheaper one was available, stocked, and just as safe. The patient didn’t notice. The doctor didn’t know. The insurer paid more. The only winner was the PBM.

This isn’t rare. It’s standard. PBMs have financial incentives to push higher-priced generics because they profit from the spread. The pharmacy gets paid, but the system loses. Patients end up paying higher copays if their plan uses a tiered system. And if the lower-cost generic isn’t on the MAC list, the pharmacy can’t even offer it without losing money.

Cost-Plus Reimbursement: A Better Model?

Some states and payers have tried a different approach: cost-plus reimbursement. Instead of setting a fixed MAC, they pay the pharmacy the actual cost of the drug plus a fixed dispensing fee - say, $4.50. This removes the spread pricing loophole. It’s transparent. It rewards pharmacies for efficiency, not for pushing expensive generics.

But here’s the problem: most PBMs hate it. Why? Because it cuts into their profits. Under cost-plus, if a generic costs $1.00, the pharmacy gets $5.50 total. No room for hidden markups. If the drug costs $3.00, they still get $7.50. The pharmacy doesn’t benefit from price inflation. So PBMs resist. They lobby. They threaten to drop pharmacies from their networks if they don’t agree to MAC-based contracts.

Independent pharmacies are caught in the middle. They need the volume from PBM contracts to survive. But those contracts often force them to stock expensive generics just to get paid. A 2022 study found that pharmacies using cost-plus models had lower generic substitution rates - not because pharmacists didn’t want to substitute, but because the financial incentive to push high-cost generics was gone. The result? More patients got the cheapest, clinically appropriate option. The system saved money. But the PBMs lost leverage.

The Consolidation Crisis

Since 2018, over 3,000 independent pharmacies have closed. Why? Narrow margins. Unpredictable reimbursement. PBMs controlling 80% of the market mean they set the rules. Small pharmacies can’t negotiate. They can’t afford to refuse a contract. So they play along - even when it means stocking a $20 generic instead of a $2 one.

Meanwhile, the three big PBMs - CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx - have grown into giants. They own pharmacies. They own insurers. They own the MAC lists. It’s a closed loop. And the result? Less competition. Fewer choices for patients. And less transparency.

Pharmacists know this. They see patients who can’t afford their meds because the generic they were switched to is still too expensive. They see patients who get confused when they’re told their "generic" costs more than the brand. They want to help. But the system won’t let them.

Therapeutic Substitution: The Real Savings Opportunity

Most people think generic substitution means swapping one brand for another brand’s generic. But the real savings come from therapeutic substitution - switching from a brand-name drug to a different generic drug in the same class that’s cheaper and just as effective.

For example: switching from a brand-name statin to a generic one might save $50 a month. Switching from a brand-name statin to a different generic statin that’s $10 a month? That saves $150. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that in 2007, therapeutic substitution could have saved $4 billion - ten times more than standard generic substitution.

But PBMs rarely incentivize this. Why? Because it’s harder to control. Therapeutic substitution requires clinical judgment. It requires doctors to approve. It requires formularies that prioritize cost-effectiveness, not profit. Most PBM formularies don’t. They’re built to maximize spread, not savings.

What’s Changing in 2025?

There’s pressure. The Federal Trade Commission is investigating PBM spread pricing. The Inflation Reduction Act now requires Medicare Part D to disclose drug pricing. Fifteen states have created Prescription Drug Affordability Boards that set Upper Payment Limits - meaning they cap how much insurers can pay for certain drugs. That’s pushing PBMs to use lower-cost generics.

Some health plans are starting to move toward value-based reimbursement. Instead of paying per pill, they pay based on outcomes. If a patient stays healthy because they’re on the right, affordable drug, the pharmacy gets a bonus. That’s the future. But it’s slow. Most pharmacies still operate under the old model: dispense as many generics as possible, hope the MAC list pays well, and pray the dispensing fee covers rent.

What Patients and Pharmacists Can Do

Patients: Always ask. "Is there a cheaper generic?" Even if your copay is low, you might be paying more than necessary. Ask your pharmacist to check the actual cost before you leave.

Pharmacists: Use your clinical authority. If a patient is on a high-cost generic and a lower-cost alternative exists, speak up. Document it. Push back on PBM formularies. Join advocacy groups like the National Community Pharmacists Association. Your voice matters.

System change won’t come from one policy. It’ll come from pressure - from patients who demand transparency, from pharmacists who refuse to be silent, and from payers who realize that the current system is unsustainable.

Generic substitution was supposed to save money. It has - but only for the middlemen. The real savings are still out there. We just need to fix the way we pay for them.

Henriette Barrows

December 29, 2025 AT 10:38I had no idea this was happening. My pharmacist always just hands me the generic without explanation, and I assumed it was cheaper for everyone. Turns out I might’ve been paying more without even knowing it. Thanks for laying this out - I’m going to start asking questions next time I pick up my meds.

Alex Ronald

December 29, 2025 AT 22:30Cost-plus reimbursement is the only ethical model here. PBMs are middlemen who add zero clinical value. If you’re a pharmacist, push for it. If you’re a patient, demand transparency. The math is simple: if the drug costs $1, you shouldn’t pay $24.50 because someone’s profit margin depends on it.

Teresa Rodriguez leon

December 31, 2025 AT 04:39This is why I hate the healthcare system. It’s not broken - it’s designed this way to bleed people dry. And nobody talks about it because the people who profit are the ones writing the rules.

Aliza Efraimov

December 31, 2025 AT 21:35Let me tell you something - I’ve worked in community pharmacy for 18 years, and this is EXACTLY what we deal with every single day. We have shelves full of generics that cost $1.50, but the MAC list says we can only get reimbursed for the $22 version. If we stock the cheap one, we lose money. If we stock the expensive one, we feel like we’re scamming our own patients. We’re not villains - we’re trapped. And the worst part? No one in insurance or government actually comes into the store to see how this plays out in real life. They just see numbers on a spreadsheet.

One woman came in last month crying because her blood pressure med went from $3 to $47 copay. She was on Medicare. She’d been on the same drug for 12 years. The PBM changed the formulary overnight. No warning. No notice. Just ‘your generic is no longer covered.’ We had to call the doctor, beg for prior auth, and still she had to wait three days. All because someone in a corporate office decided to maximize their spread.

Therapeutic substitution isn’t just a buzzword - it’s lifesaving. But it requires trust. Trust between doctor and pharmacist. Trust between pharmacist and patient. And right now, the system is built to destroy that trust. We’re not just dispensing pills - we’re trying to hold together a system that’s falling apart.

And yeah, I know I sound dramatic. But when your patients skip doses because they can’t afford the ‘generic’ you’re forced to give them, you learn to speak up.

Nisha Marwaha

January 1, 2026 AT 16:33The structural inefficiencies in the PBM-MAC ecosystem are a textbook case of principal-agent misalignment. The pharmacy (agent) is incentivized to optimize for reimbursement metrics rather than clinical cost-effectiveness, while the payer (principal) is unaware of the actual cost structure due to opacity in spread pricing. The result is suboptimal therapeutic outcomes and distorted price signals in the pharmaceutical supply chain. Cost-plus reimbursement realigns incentives by decoupling dispensing fees from drug acquisition cost, thereby eliminating perverse incentives for formulary manipulation.

Amy Cannon

January 2, 2026 AT 07:28It's just... wow. I mean, I knew things were bad, but this? This is like someone took the entire healthcare system and ran it through a blender with a spreadsheet and a corporate powerpoint. I had no idea that a $1.20 pill could be swapped for a $24.50 one and no one would notice. Not the doc. Not the patient. Not even the insurance guy. It's like we're all playing a game where the rules were written by people who don't even know what a pill looks like. And the worst part? We're all just supposed to be grateful that we're getting 'generic' medicine. Like that's some kind of win. I mean, if I bought a car and they swapped my $20,000 Toyota for a $22,000 Toyota and said 'you're saving money!' I'd call the cops. But with medicine? We just nod and pay.

Himanshu Singh

January 4, 2026 AT 07:07soo many people dont even know this is happening. i live in india and we have cheap generics everywhere but here in us its like a joke. why is this so hard to fix? also i think pharmacists should get paid more directly instead of being stuck in this pmb mess. they are the real heroes.

Jasmine Yule

January 4, 2026 AT 08:11My mom just got hit with a $60 copay for a generic she’s been on for 5 years. I called the pharmacy. Turns out the PBM changed the MAC list last week. The drug is still the same. The pill is the same. But now it’s ‘not covered’ unless she pays triple. I’m furious. And I’m not even the patient. I just want to scream at someone. Who do we even fight? The PBM? The insurer? The pharmacy? We’re all just trying to survive this.

Jim Rice

January 5, 2026 AT 15:57Actually, this whole post is misleading. Pharmacies make money on generics because they’re high volume. The MAC system isn’t broken - it’s efficient. If you want cheaper drugs, stop demanding brand names. And stop blaming PBMs. They’re just responding to market demand. Also, cost-plus reimbursement leads to pharmacy closures because they can’t cover overhead. This isn’t a conspiracy - it’s capitalism.

Manan Pandya

January 6, 2026 AT 02:32Jim, you’re missing the point. Efficiency doesn’t mean fairness. The MAC system isn’t about volume - it’s about extraction. Pharmacies are forced to stock expensive generics to stay in-network, even when cheaper alternatives exist. That’s not market demand - that’s market coercion. And cost-plus models have been proven to reduce waste and improve adherence. The closures you mention? Those happened because PBMs slashed reimbursement rates and refused to negotiate. It’s not capitalism - it’s monopoly.

Paige Shipe

January 6, 2026 AT 02:32It's clear that the author has a biased perspective against Pharmacy Benefit Managers. The truth is that PBMs negotiate bulk pricing and manage formularies to ensure access to medications. Without them, patients would pay even more. The system is complex, yes, but it's not malicious. Pharmacists are compensated fairly under the current structure. This narrative is emotionally manipulative and lacks data from actual pharmacy financial statements.

Tamar Dunlop

January 6, 2026 AT 12:20As someone who has practiced pharmacy in both Canada and the United States, I can attest that the disparity in reimbursement structures is staggering. In Canada, the provincial formularies are transparent, and reimbursement is largely cost-plus with minimal spread. The result? Consistent access, lower out-of-pocket costs, and pharmacists empowered to make clinical decisions. In the U.S., the commercialization of pharmaceutical distribution has transformed healthcare from a public good into a profit-driven enterprise. The moral imperative here is not merely economic - it is ethical. We must restore the primacy of patient care over corporate margins, or we will continue to witness the erosion of trust in the healthcare profession.